Back in May 2017, I took a solo backpacking trip through Georgia and Armenia. In the lead-up to the trip, a lot of friends and family asked me to text them along the way “to let them know I was still alive”.

It was mostly a joke (?), but it still felt like an odd request, and the frequency was uncanny. I’m of the opinion that both Georgia and Armenia are (a) incredibly safe, and (b) full of ludicrously hospitable people, so the concern from my friends and family seemed a little undue.

In that moment, something had stuck in my head from the era when people were registering random domain names to answer a single question – does australia have a government yet .com is regarded as a 2010 classic1, and has brexit happened yet is… somehow even in July 2019 still a relevant example.

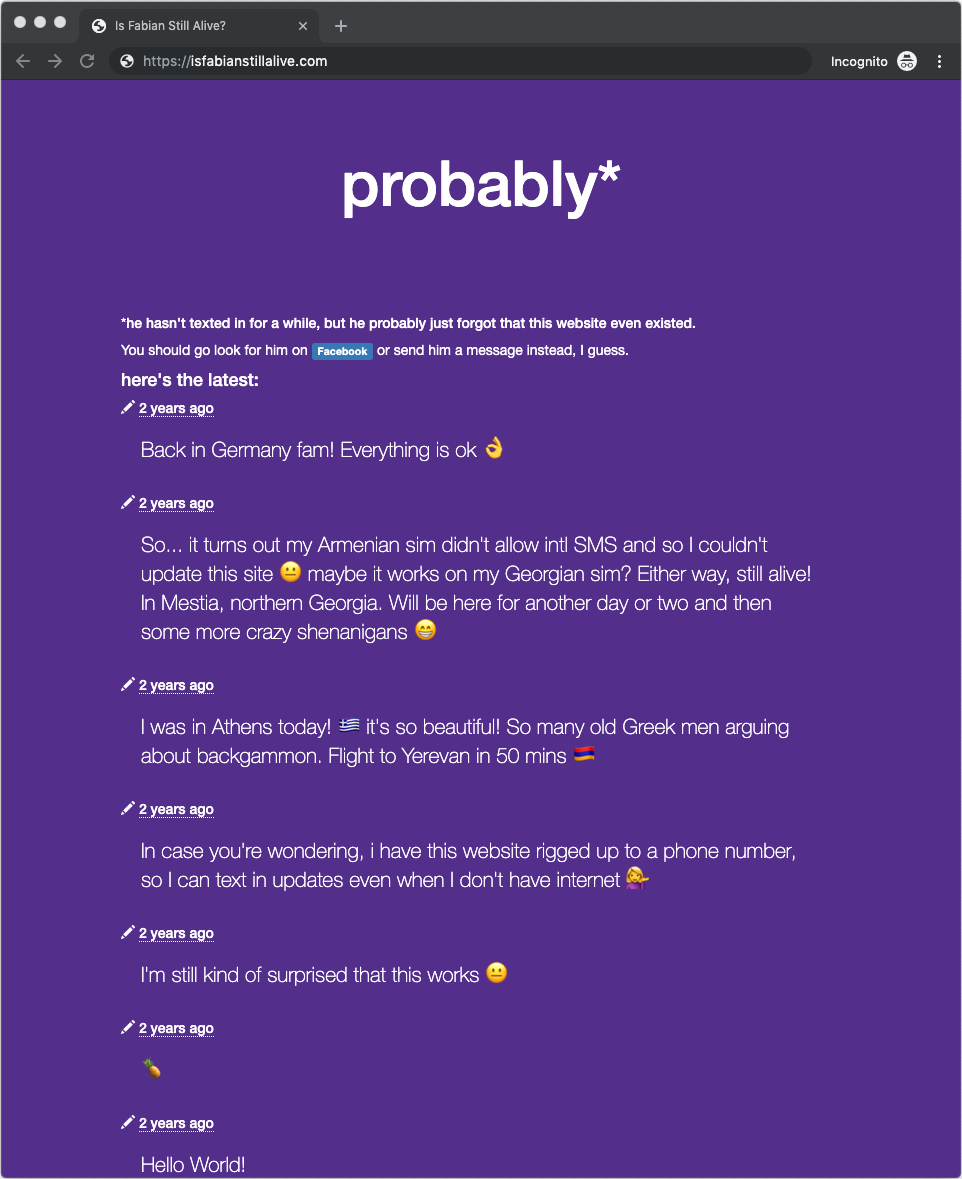

So, instead of actually texting my friends and family, I set up a handy reference guide at an easy-to-remember URL:

A screenshot of isfabianstillalive.com, from 2019, well after returning.

probably*

“probably*” is the best possible answer to this question. It’s still a pretty accurate guess, even today!

How does it work?

I was pretty sure I wouldn’t have internet access the whole time I was in the mountains in Georgia and Armenia, but thought that basic mobile reception was likely, so I set up a programmable phone number on Twilio, which passes the SMSes along from the phone to my server2.

Each message you see in the above screenshot started off as a text message on my phone.

I was especially thrilled that the system just seemed to handle emoji without any trouble (hence the 🍍 in the second message)3.

The one thing I didn’t anticipate was that I often found myself in situations with perfect data – like in the forest on the side of a mountain, downloading 30 MB of maps so I could find the trail again4 – but without the ability to send international SMSes to the US-based Twilio number. I feel like I learned an aversion to assuming that software would “just work” sometime during that trip.

Mestia and surrounds, Georgia. Looks like a fairytale, has 25 Mbps wireless data.

Intentionality, slow media, and community

It’s now July 2019, and I’m writing this note after having decided that it was time to build an online home for some of my more recent, smaller projects. Over the last few months, Craig Mod has been writing about a walking trip he did along an old highway, in his (now-) home country of Japan. I first found out about his writing when he’d finished the hike, but discovered much later that he, with some friends, had built an SMS-based micro-publishing system to keep people updated along the way. I think there’s something super cool about reclaiming your attention span and breaking the feedback loops of social media5, while still being able to keep people all over the world updated. I like that there’s a really explicit reward loop – a book of responses to look forward to at the end. It’s like all of the instant gratification compressed, such that the effort is expended over weeks, and the payoff is a physical artefact of the ways in which people interacted with what you were seeing and doing. It reminds me of printing and mailing photos from my Germany - Italy hike last year to my Nan, and receiving a letter in response a month later. This syle of feedback is so deep.

Craig’s project feels a little like “Is Craig Mod Still Alive Dot Com”, but set up with a lot more intentionality.

I think this level of intentionality is often absent from the way we use technology – the trope is that many tech companies are incentivised to keep us stuck in tiny, tiny feedback loops – but, I wonder if it’s like any other addiction. You can’t shake something only by focussing on how much you don’t want it; you need to fill that space with something rich and meaningful.

Darius Kazemi published a guide a few weeks back on How to Run Your Own Social Network. The overwhelming refrain in this guide is:

Running a social network site is community building first and a technical task second… and while community building is hard work, it’s often worth it.

There are parallels here. The people are the social network. The specific technology is a medium, and the medium affects the message, especially at scale. But ultimately, the degree to which the things you create are created for people affects the depth of the reward. Intentionality around the communications tools you’re using and an understanding of the way they shape the community around you is important, because they’re the tools by which you shape and edify your community.

This was politically fascinating – it was the first time since World War II that neither of the major Australian political parties was able to form government alone, which resulted in an unusually drawn-out negotiation process until the Labor party eventually formed government. This election had everything: it was the re-election of Australia’s first female prime minister, and took place just after the first of a series of governmental leadership spills, which are now regarded as an Australian tradition. It apparently also followed a legal judgement that resulted in 100,000 previously unregistered voters suddenly being entitled to enrol before the election. There’s a good writeup on the Australian Parliament House website. ↩︎

If you’re a code person, the source is hosted at github.com/capnfabs/isfabianstillalive. ↩︎

Character encoding is really hard. I wrote something about how SMS specifically represents emoji here. ↩︎

In retrospect, maybe the concern from my friends and family was more to do with me than with the countries I was visiting. ↩︎

There are lots of good books in this space. The Shallows by Nicholas Carr was one of the first, and is uncanny in its prescience, and Deep Work and Digital Minimalism are good, more practical treatises, if you’re willing to tolerate the arrogance in the Author’s tone and the fact that both carry a strong undertone of male chauvinism. ↩︎