Information Technology - it’s an awfully un-glamourous pair of words. When people think of IT, they think of business applications that don’t really work as well you’d expect them to, database administration, and ugly-looking spreadsheet-y things on badly designed websites.

I’m moving into a software development job next year, and I so badly want to rush to tell people that IT is not what I do. The thought makes me cringe, and I’m not sure why. It’s not the stereotypes (ok, it’s a little bit the stereotypes); it’s a deep desire to be known for doing something that’s meaningful.

It’s surprising that information technology makes me cringe because information is awesome! Information helps us make decisions. If you told me it was going to rain tomorrow and I somehow remembered to pack an umbrella, hooray! Information saves the day! If I told you that a guy on the street outside was giving away iPhones, and he was, woohoo! Information! If you call the fire brigade, and tell them exactly where the fire is, and they turn up in time, boo-ya! Information!

So why does information technology suck so hard?

Information ≠ Data

The problem is that the phrase ‘Information Technology’ has somehow come to refer to data technology.

Let me stress:

Information ≠ Data

Data is little bits and pieces of truth (hopefully). Tiny little factoids, interesting at best, useless at worst.

Information is relevant data: data that is useful for making decisions. As such, all information has context, and needs to be communicated effectively. Without fulfilling these two criteria, it’s just data.

Information has Context

Information has context and gets interpreted in context. Because information is interpreted in context, it needs to be underpinned by identical assumptions, timely and relevant.

Take our umbrella example before. It was fantastic when you told me that it was going to rain tomorrow, but we both assumed that we were talking about the same place. If instead, you were referring to the weather in Madrid, the data is useless - it’s not information.

Take our guy on the street giving out iPhones - if I waited until a week from now to tell you about him, you’d probably just be annoyed. Maybe it would make for a good story, but it certainly doesn’t affect the way you live. Without timeliness, data is an interesting story at best.

Take our fire-brigade example. If instead, I picked up my phone, dialled somebody at random, and told them exactly where the fire was, it wouldn’t be particularly useful. Delivering data to the wrong people stops it from becoming information.

A good test to see whether data is information is to see whether you could legitimately ask “why are you telling me this?”. If you can, you’re working with data, not information.

Information is well-communicated

If information is useful data, then it needs to be communicated in a fashion that empowers people to make decisions.

Take this data for example:

35% more men than women like to wear pirate hats on tuesdays.

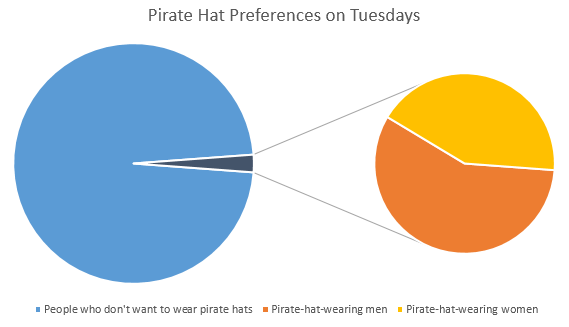

This information might be useful to pirate hat salespeople, for example, who might reason that they’d be better off targeting men instead of women on Tuesdays. That’s a valid conclusion, but this single figure doesn’t tell the whole story. The above statistic came from the following data:

On Tuesdays, 1% of women like to wear pirate hats on a Tuesday.

On Tuesdays, 1.35% of men like to wear pirate hats on a Tuesday.

Not looking so good for our pirate hat salespeople any more! (Especially if interpreted within the context of a salesperson’s knowledge that 10% of all people like to wear pirate hats on Saturday).

The problem with the first fact isn’t the truthfulness of the data - it’s that the first fact oversummarises - it throws away too much data for the sake of brevity, because of a lack of context-awareness.

In most situations, a well-designed graph will give you the desired level of simplicity, whilst retaining the richness of the data you started with:

Pirate hat interest on Tuesdays (graph)

The pirate hat salespeople would find something like this far more powerful for effective decision-making. Even then, it might be more relevant to slice the data based on day of week, and track interest over the week instead of between genders on a single day.

…and back to Information Technology

All of this should be fairly intuitive (if a little difficult to articulate) - what I’ve presented here is just a few key principles of effective communication. ‘Information Technology’ often falls short when it comes to effective communication, and that’s why people still think about it as ‘data technology’.

Information is awesome - there’s little doubt about that. As an Information Technologist, it’s my job to help people to make good decisions by communicating meaningful, context-appropriate data. That’s something I’d be happy to do.